For a pdf of this session, please click here.

The world is changing. A key change for the church is what is sometimes referred to as the end of Christendom. It is no longer true to say that this country is a Christian country where everyone is, at least nominally, a Christian and where the church’s duty is to pastor the flock—that is, everybody. Stuart Murray writes:

Total ignorance of church and Christianity may not yet be widespread, but it is becoming more common, especially in our inner cities. Over the coming decades, as the last generation who are familiar with the Christian story and for whom churches still have cultural significance dies, the change of epoch from Christendom to post-Christendom will be complete. (Murray 2004:2)

Murray argues that the shift away from Christendom to Post-Christendom entails a number of other shifts:

From centre to margins—in Christendom the Christian story and the churches were central, but in post-Christendom these are marginal.

From majority to minority—in Christendom Christians comprised the (often overwhelming) majority, but in post-Christendom we are a minority.

From settlers to sojourners—in Christendom Christians felt at home in a culture shaped by their story, but in post-Christendom we are aliens, exiles and pilgrims in a culture where we no longer feel at home.

From privilege to plurality—in Christendom Christians enjoyed many privileges, but in post-Christendom we are one community among many in a plural society.

From control to witness—in Christendom churches could exert control over society, but in post-Christendom we exert influence only.

From maintenance to mission—in Christendom the emphasis was on maintaining a supposedly Christian status quo, but in post-Christendom it is on mission within a contested environment.

From institution to movement—in Christendom churches operated mainly in institutional mode, but in post-Christendom we must again become a Christian movement. (2004:20)

Although it is relatively easy for Christians to acknowledge the death of Christendom it is much harder to accept just how radical a shift in our thinking, and practice is really demanded by its implications. The majority of church folk, including church leaders, still continue as if Christendom was still in its pomp.

In particular, the death of Christendom means that there are increasing numbers of people who have had no meaningful contact with church and who have no knowledge of even the basics of the Christian faith. If we are reach out to them there will need to be some fairly radical rethinking of what it means to be the church in the world.

Tom Sine (2008) has identified four streams within the global church which are trying to engage in this radical rethinking. He labels these emerging, missional, mosaic and monastic. The major emphasis in this session is the emerging stream and we will also take a brief look at the monastic stream. For completeness, brief descriptions of missional and mosaic follow:

The missional stream is best exemplified in this country by Fresh Expressions. It springs firstly from a renewed understanding of the Great Commission (Matthew 28:18-20; John 20:21; Acts 1:8). And, even more, it springs from an understanding of the missionary nature of God:

It is not the church that has a mission of salvation to fulfil in the world; it is the mission of the Son and the Spirit through the Father that includes the church. (Moltmann 1977:64)

As Rowan Williams said,

I think the work that’s being done through the Fresh Expressions initiative already, in just over a year, has been phenomenal. I think we’ve got a very gifted, a very committed team, we couldn’t have done better. And everywhere we turn there is encouragement. It does seem that God is doing things already with the life of the Church in this country. And if it’s true that mission, as it has been said, is finding out what God is doing and joining in, then we’ve certainly got a lot of joining in to do and that’s wonderful.

There is now a large literature on Fresh Expressions of Church, starting with the seminal Mission-Shaped Church report (Cray 2004).

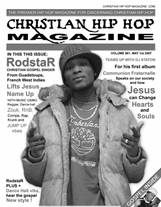

The emerging church movement is predominantly white and middle class. Mosaic is a term coined by Tom Sine to cover a range of new churches where this is not true. He reports that there were at least twenty hip hop churches in the USA by 2008. There is also a growing number of churches in the States which deliberately set out to be multicultural, sometimes focused on mixed race people who do not feel comfortable in either black or white churches, sometimes deliberately setting out to celebrate the diversity of God’s creation.

In the UK, the fastest rate of church growth is among Pentecostal Churches, whose congregations are largely drawn from African communities in London. Between 1998 and 2006 they started nearly 500 churches. For instance, The Redeemed Christian Church of God, a Nigerian-based group, is one of the fastest growing black churches with 210 ‘parishes’ across London.

Perhaps the most coherent practical response to changing Western culture is what is commonly known as the emerging church. The term appears to have first been used by Bruce Larson & Ralph Osborne in 1970. They saw a new kind of church emerging, a church in which ‘and’ is an important word. The emerging church is an umbrella term given to a range of new congregations which are trying to be church in a postmodern world. Emerging church is a movement rather than an organisation or denomination—indeed, many prefer to refer to it as a ‘conversation’ about ways of doing church in an unchurched world and there have been a number of writers and practitioners who have influenced its development.

Pete Ward, in his thought-provoking Liquid Church, looks forward to the emergence of a new kind of church which is able to engage with the unchurched generations. He stresses that this does not yet exist but feels that something like it needs to come into being if the church is to survive in the new emerging culture of the West. One of the shifts which Ward foresees is a move from noun to verb, from state to process:

…I suggest that we need to shift from seeing church as a gathering of people meeting in one place at one time—that is, a congregation—to a notion of church as a series of relationships and communications. (2002:2)

We should start thinking of church as an activity rather than a place or a fixed community. We make the same sort of distinction when we talk of being in fellowship or being a fellowship; the former is liquid, the latter is solid.

Solid church focuses on attendance at services—the more often you attend the more committed and faithful you are; size—the bigger the congregation, the more successful it is; one size fits all—solid church tends either to be stuck in middle-of-the-road position in terms of theology and worship (don’t offend anybody!) or it is explicitly committed to one worship style or theological orientation; and joining the club—you are either ‘in’ or ‘out’.

Liquid church, by contrast, is networked, dispersed, consumer-oriented and evanescent. Ward draws on J. D. G. Dunn’s views on Paul’s use of the phrase “in Christ” and its importance in creating the identity of the church:

The identity of the Christian assembly as a “body,” however, is given not by geographical location or political allegiance but by their common allegiance to Christ (visibly expressed not least in baptism and the sacramental sharing in his body).

Ward argues that anyone ‘in Christ’ is in the church, so that the church can effectively be thought of as a star network with Christ as the hub. He also sees support for his notions of liquidity in the notion of perichoresis (inter-penetration) used by the Cappadocian Fathers to describe the relationships between the members of the Trinity.

Ward claims that much of contemporary culture is a pursuit of purpose. Shopping, for example, is seen as searching for meaning rather than selfish materialism—and the church should accept the challenge implied by this. Liquid church moves from meeting need (the need for God, etc.) to satisfying desire—since consumerism is essentially about the desire for meaning and spirituality.

One of the most influential voices in the debate about new ways of being church is that of Brian McLaren who was nominated by Time magazine in 2005 as one of the 25 most influential evangelical leaders in the US. Each leader had a catch phrase to identify him (Jim Packer was “Theological Traffic Cop”)—McLaren was billed as “Paradigm Shifter”.

McLaren has written a number of books; perhaps the most significant have been the “New Kind of Christian” trilogy (2001, 2003 & 2005). Written as novels, they describe the journey of Dan, an American pastor, from his traditional evangelical roots to an understanding of postmodernism and the emerging church. McLaren’s books are easy to read and quite seductive in their tone; they try hard to find a ‘third way’ between conservative and liberal positions and don’t always succeed.

The immediate impact of McLaren’s writings on the unchurched is doubtful. His major influence seems to be within the growing numbers of American evangelicals who are growing disillusioned with the right-wing doctrinaire versions of reformed theology and practice to be found in the States. It is these people who are being led to engage more directly with the unchurched and to start their own emerging congregations.

Many emerging churches are associated with the alternative worship movement (see session seven), which itself traces its roots to the Nine O’clock Service at St Thomas in Crookes, Sheffield. It is probably true to say that the UK has taken the lead in this area though there are emerging churches in the US, Australia & New Zealand as well. Many of the emerging church leaders come from an evangelical background and some may still be happy with that label but all have gone far beyond the boundaries of traditional conservative evangelical orthodoxy and practice—while still considering themselves to be true to the foundations of their faith.

Peter Rollins (2006:5ff) suggests that emerging churches share a concern for the notion of journeying and becoming. He also argues that the emerging church is not just looking for a new way to present traditional beliefs in a contemporary context but it actually seeking to look again at the way we believe:

In short, this revolution is not one which merely adds or subtracts from the world of our understanding, but rather one which provides the necessary tools for us to be able to look at that world in a completely different manner: in a sense nothing changes and yet the shift is so radical that absolutely nothing will be left unchanged. (2006:7)

The most important work on the emerging church so far is probably Emerging Churches by Eddie Gibbs and Ryan Bolger who interviewed 50 emerging church leaders in the UK and US. They characterise emerging churches as “communities that practise the way of Jesus within postmodern cultures” (2006:44). They are clear about what they mean by modernity and postmodernity:

Modernity began with the creation of secular space in the fourteenth century. This sacred/secular split led to fragmentation in society simultaneously with the pursuit of control and order. Postmodernity marks the time when secular space was called into question concurrent with the pursuit of holism and the welcoming of pluralization in Western societies. (2006:44)

According to Gibbs & Bolger there are nine ‘practices’ which characterise emerging churches. The three core practices are that they:

Identify with the life of Jesus;

Transform the secular realm;

Live highly communal lives.

Because of these three, they also:

Welcome the stranger;

Serve with generosity;

Participate as producers;

Create as created beings;

Lead as a body;

Take part in spiritual activities.

Here there is only space to look at the three core practices and to indicate a little of their distinctiveness and implications.

The emerging church has a distinctive focus on the life of Jesus, something perhaps more characteristic of Orthodox churches than Western churches, whether Catholic or Protestant. This leads to a number of emphases:

Most emerging church leaders come out of an evangelical background and are used to the conservative evangelical emphasis on the Epistles and the Old Testament. Perhaps in reaction to this, they tend to focus on the Gospels and the work and teaching of Jesus. Some American emerging church members draw attention to themselves as “Red-letter Christians”; that is they focus on the words of Jesus (printed in red in some Bibles) as opposed to the black letter words of people like Paul. Although most would see this as a false dichotomy, it can serve as a useful corrective against an unhealthy ignoring of the gospel accounts of Jesus’ life, teaching and ministry.

Perhaps the key consequence of this focus on Jesus is a renewed emphasis on the kingdom of God. Following writers such as N. T. Wright (1992, 1996, 2007) and Dallas Willard (1998), the emerging church has adopted a theology of kingdom, sometimes opposing it to a theology of salvation (though the two are not mutually exclusive, of course). A phrase which is sometimes used to emphasise this is Jesus did not come to take us to heaven, he came to bring heaven to us. Brian McLaren’s The Secret Message of Jesus is a recent (2006) exposition of this renewed interest in Jesus’ teaching about the kingdom.

The focus is on exploring kingdom living here and now, rather than a future salvation in heaven. Dieter Zander is at Quest in Novato, California. He parodies the modern church in this way:

Give a little

Do a little

Pay membership dues

Get a “going to heaven” ticket (through accepting the gospel).

In this scenario the gospel is informing how we die. Instead, the gospel ought to be about how we live! A lot of church people don’t know the relationship between the gospel of Jesus and how we are to live. They are threatened by re-evaluating that. Their belief is that they try to believe in Jesus so that when they die they get to heaven. Populating heaven is the main part of the gospel. Instead, the gospel is about being increasingly alive to God in the world. It is concerned with bringing heaven to earth. (Gibbs & Bolger 2006:55)

Despite its name, the emerging church is wary of the term ‘church’. Jesus didn’t form churches, or call us to do so, they would argue. What he wanted was kingdom communities committed to work with God on the project of bringing the kingdom which is ‘at hand’ a little closer. In this view, the Sermon on the Mount is not a set of impossible ideals pointing the way to a future perfect live in heaven but a practical manifesto which Jesus was deadly serious in laying before the world as the only way to live.

Many emerging church leaders are sceptical about much modern evangelism. They feel that it offers a ‘sugar-coated’ gospel of cheap grace to entice people in and only them confronts them with its costliness. This is seen as cynical and dishonest, and therefore dishonouring to Jesus. Instead many groups are up front about their commitment to justice and community action and their desire to live lives of forgiveness and servanthood which are transformed by their relationship with Jesus. Values are important and if honesty is one of your values you cannot hide even if it might be unattractive to potential converts.

The notion of Missio Dei, which could crudely be characterised by the phrase, “find out what God is doing and join Him”, is important. Mission is God’s work, not ours and the emerging church tries to discern the movement of the Spirit and to join in. Jesus implies as much when he said,

Truly, truly, I say to you, the Son can do nothing of Himself, unless it is something He sees the Father doing; for whatever the Father does, these things the Son also does in like manner. (John 5:19)

Just as Jesus was incarnate in a specific culture and set of social circumstances, so each emerging community aims to exemplify incarnational engagement with the culture in which they find themselves.

Because of this commitment to incarnational engagement, emerging churches either deny, or try to break down, what they see as an artificial split between secular and sacred. Many would agree with this quote from Madeleine L’Engle (2001):

There is nothing so secular that it cannot be sacred, and that is one of the deepest messages of the incarnation.

In other words, they challenge the notion that there are some areas of life in which God has no part, agreeing with Psalm 24—”the earth is the Lord’s and everything in it”. To some extent this resonates with the holistic notions taken up so enthusiastically by many in the alternative spirituality movement.

Emerging churches have no hesitation in using music, film or literature from popular culture in their worship; it is neither more nor less important than ‘religious’ art. Emerging worship is often playful, sometimes irreverent, and can be disturbingly nonlinear to those broad up on a diet of solidly predictable liturgy. But because this is often a faithful reflection of the fragmented nature of contemporary culture it is embraced as an authentic and incarnational spirituality. Scripture reading and study, preaching and proclamation are similarly transformed and the last four sessions of this course will explore aspects of these in greater detail.

Martin Luther apparently once said that, “The ears are the only organ for the Christian.” Unlike many in the church, emerging communities are not prepared to ignore today’s highly visual culture; instead they embrace it, determined to restate the truths of the gospel in ways which engage all the senses. It is for this reason that emerging worship contains smells, icons, and things to touch and taste as well as words and music.

Not only do the emerging churches reject the sacred/secular distinction, they also wish to embrace both transcendence and immanence. As Peter Rollins says,

What is beginning to arise…is the idea that God ought to be understood as radically transcendent, not because God is somehow distant and remote from us, but precisely because God is immanent. In the same way that the sun blinds the one who looks directly at its light, so God’s incoming blinds our intellect. In this way the God who is testified to in the Judeo-Christian tradition saturates our understanding with a blinding presence. (Rollins 2006:24)

This leads to a desire to celebrate both the mystical and the mundane aspects of life in all their fullness.

The Nine O’clock Service (NOS) in Sheffield is often credited as the real start of the emerging church movement; at its heart was a Christian community. Influenced by David Watson, a young couple called Chris and Winnie Brain started the Nairn Street Community in Sheffield in the early 1980s. This involved about 30 people who lived in a number of houses in the city and who shared their incomes, read the Bible together, prayed and shared issues in the personal lives. (NOS started after a John Wimber visit to St Thomas in 1995 when Robert Warren, the vicar, asked Chris Brain and his band Present Tense to lead a service at Nine O’Clock on Sunday evening.)

This desire for community is characteristic of the emerging church. Church is seen as kingdom community because Christ’s call to kingdom living means the dissolution of all pre-existing ties (“Who is my mother, and who are my brothers?”, Mt 12:48; c.f. Mt 10:35). Church does not exist for itself but only as a (passing) expression of kingdom community here on earth. (The movement often known as the ‘New Monasticism’ takes this theme very seriously—see below.) Thus being church is all about learning to live as Jesus taught us.

The challenge is both to the selfish individualism of contemporary society and to the establishment church’s focus on individual salvation and holiness. This is one reason why emerging churches often use dance music. The clubbing experience is often experienced in a corporate way which is very different from the experience of rock and pop music.

Because the focus is not on the church but on the kingdom, emerging churches rarely worry about numbers or other marks of ‘success’. As Mark Scandrette of REIMAGINE! in San Francisco put it:

I am on a journey to find where heaven and earth come together in order to really experience the gospel. The goal of this is to see the gospel expressed, not necessarily in any terms of budget or number goals. (Gibbs & Bolger 2006:94)

Relationships are often expressed in terms of family rather than institution. Andrew Jones of Boaz, a New Zealander who is currently starting a monastery in Orkney:

I believe the commitment is more relational than institutional. Emerging people commit to one another and to God, and that commitment is deep and lasting. We are stuck together as family, even if we don’t like one another. (Gibbs & Bolger 2006:97)

Relationship takes precedence over place. The gathering is no longer the most important aspect of church. Simon Hall of Revive in Leeds expresses this well:

We’re moving towards membership of Revive having nothing to do with attending a particular meeting. Instead it’s about being accountable (through a small group, prayer triplet, soul friend, spiritual director, etc.) to five basic values of discipleship. There is no law (you shall pray for this length of time, four times a day), but there is a sense of movement (this is my next step in following Jesus). (Gibbs & Bolger 2006:105)

A local example is Ambient Wonder, an emerging church operating out of St Augustine’s, Norwich. This is how they describe themselves:

As you’d expect ambient wonder is about relationships. with each other and with God. When we get together to do an event we have certain values. These include a commitment to using all of our senses, drawing on the creativity within all of us and an expectation that the event is about creating space to explore and experience rather than to prescribe and give answers. Our website will give you more information on what it looks and feels like to be at one of our gigs.

These values are equally reflected in how we plan and organise. We look to involve as many people as possible, expect to learn from everybody and don’t have a single “leader” of ambient wonder. We draw on a pool of people who’ve said they’ll help put an event on. For an event one person will have the role of curator, a bit like in an art gallery, whose role will be to draw together the contributions of others and create the space for those who come to encounter God. (www.ambientwonder.org)

The emerging church is an attempt to find ways of responding authentically to the call of Jesus in the 21st Century. It rejects some of what has been considered orthodox for the last few hundred years. It also affirms and transforms much which has been in the church since the very beginning.

The keywords of the emerging church include kingdom, authenticity, relevance, creativity and community. There is much that can be criticised but also much which offers a way forward for the church as a whole. The movement has already influenced the mainstream church more than most people recognise. It will continue to do so.

The final stream picked out by Tom Sine is monasticism—often known as ‘new monasticism’, perhaps in response to Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s comment in a letter to his brother:

The renewal of the church will come from a new type of monasticism which only has in common with the old an uncompromising allegiance to the Sermon on the Mount. It is high time men and women banded together to do this.

The movement appears to have its roots in the late 70s and early 80s in both the UK and US but it was not until 2004 that a meeting of groups at St. Johns Baptist Church in Durham, North Carolina formalised the overarching title ‘new monasticism’. They came up with a set of twelve marks of the movement:

Relocation to the abandoned places of Empire.

Sharing economic resources with fellow community members and the needy among us.

Hospitality to the stranger.

Lament for racial divisions within the church and our communities combined with the active pursuit of a just reconciliation.

Humble submission to Christ’s body, the church.

Intentional formation in the way of Christ and the rule of the community along the lines of the old novitiate.

Nurturing common life among members of intentional community.

Support for celibate singles alongside monogamous married couples and their children.

Geographical proximity to community members who share a common rule of life.

Care for the plot of God’s earth given to us along with support of our local economies.

Peacemaking in the midst of violence and conflict resolution within communities along the lines of Matthew 18.

Commitment to a disciplined contemplative life.

At the heart of the new monasticism is a desire to live in kingdom communities of people who want to live a common life. But most new monastic communities do not share a common living space, though they are often situated in close geographically proximity.

Another characteristic of new monastic communities is that they, in common with traditional monasticism, submit to a rule of life. This is rarely the traditional ‘three knot’ rule of poverty, chastity and obedience. Instead each community adopts a rule which seems to be appropriate for their circumstances. For instance, ‘smallboatbigsea’ in Australia have what they call a Weekly Rhythm with the acronym BELLS:

BLESSING: Who have you blessed this week through words or actions and what learning, encouragement or concerns were raised by it?

EATING: With whom have you eaten this week and what learning, encouragement or concerns were raised by it?

LISTENING: Have you heard or sensed any promptings from God this week?

LEARNING: What passages of Scripture have encouraged you or what other resources have enriched your growth as a Christian this week?

SENTNESS: In what ways have you sensed yourself carrying on the work of God in your daily life this week?

The Northumbria Community’s rule is very simple: ‘The Rule we embrace and keep will be that of AVAILABILITY and VULNERABILITY.’ They go on to say:

As a geographically dispersed Community our Rule of life is deliberately flexible and adaptable, so that it does not prescribe uniformly, but provokes individually. It is descriptive rather than prescriptive in that it encourages seeking God for oneself, who we are, where we are, what we are, so as to be a sign of vulnerability, a sign of availability, wherever we are as a scattered Community.

In this session we have used Tom Sine’s classification looked at some of the responses to the changing world in which the church finds itself. But the demarcations between them are not clear and there is much overlap. What we are seeing is a creative exploration of what it means to be church today. The journey will continue until the kingdom comes.

The first chapter of Murray 2004—Post-Christendom can be found online at

http://www.opensourcetheology.net/node/361

The Rowan Willams quote comes from the transcripts of a radio interview on 8th December 2005. The full text can be found on the Fresh Expressions website or at

http://www.archbishopofcanterbury.org/976

The quote from Dunne is cited by Ward 2002:35 and comes from Dunne 1998:551.

For more on perichoresis, see Greenwood 1994:77 ff.

The full list of Time’s 25 evangelical leaders was Howard & Roberta Ahmanson; David Barton; Doug Coe; Chuck Colson; Luis Cortès; James Dobson; Stuart Epperson; Michael Gerson; Billy & Franklin Graham; Ted Haggard; Bill Hybels; T.D. Jakes; Diane Knippers; Tim & Beverly LaHaye; Richard Land; Brian McLaren; Joyce Meyer; Richard John Neuhaus; Mark Noll; J.I. Packer; Rick Santorum; Jay Sekulow; Stephen Strang; Rick Warren and Ralph Winter.

Brian McLaren on The Secret Message of Jesus:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5udKP9Q4_jw&mode=related&search= (6 mins)

If

you want to know more about hip hop church, a book worth reading (I haven’t)

may be Smith, Efrem & Jackson Phil The Hip-Hop Church: Connecting with the

Movement Shaping Our Culture (Paperback).

If

you want to know more about hip hop church, a book worth reading (I haven’t)

may be Smith, Efrem & Jackson Phil The Hip-Hop Church: Connecting with the

Movement Shaping Our Culture (Paperback).

Among hip hop churches, Crossover Church in Tampa, Florida (“Our Sole Purpose is to Give Your Soul Purpose”) can be found at

http://crossoverchurch.org/home.html#

For some images of mass at the Harlem Hip Hop Church, see

http://pa.photoshelter.com/c/dbrabyn/gallery-show/G0000C888B5j6lgI/

In the UK the Black Majority Church Directory (http://www.bmcdirectory.co.uk/) gives details of hundreds of black majority churches. It estimates that there are more than 500,000 Black Christians in over 4,000 local congregations in the United Kingdom, the majority of whom are in England, and the majority of them in London.

For an account of the rise and fall of the Nine O’clock Service see Howard 1996. It is a secular journalistic account but seems reasonably fair and sympathetic.

Gibbs & Bolger (2006) do not include some churches which characterise themselves as emerging such as Mars Hill in Seattle (http://www.marshillchurch.org). This is because although Mars Hill is focused on reaching out to postmodern young people in a missional way, its theology is firmly in the reformed conservative evangelical tradition. Mars Hill also embraces the mega-church perspective (it has about 4000 members), which is not typical of emerging churches. Mark Driscoll’s approach to emerging church can be found here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RcbnGXSYxuI

“John Travis” (a pseudonym) developed a ‘contextualisation spectrum’ to describe different kinds of church in Muslim contexts. Greg Allison uses this spectrum to look at different kinds of church within contemporary Western Culture, suggesting that emerging churches occupy a number of different positions on the spectrum: http://www.theresurgence.com/gospel_culture_and_church/church_stuff/emergent

The term ‘Red Letter Christian’ has been a adopted by a politico-religious grouping in the US. It includes people like Brian McLaren, Tony Campolo and Jim Wallis. For more information see What’s a ‘Red-Letter Christian’? by Tony Campolo at http://www.beliefnet.com/story/185/story_18562_1.html or Red Letter Christians: Somehow, Jesus Has Survived Even the Church by Jim Wallis at http://www.sojo.net/index.cfm?action=magazine.article&issue=soj0603&article=060351

Not everyone is happy with this alliance. For a critique see ‘Red Letter’ Liberal Christians: A New Front Group For Democrats By Rev. Louis P. Sheldon, Chairman, The Traditional Values Coalition at http://www.traditionalvalues.org/modules.php?sid=2867

It is hard to track down the origin of the “Jesus did not come…” phrase. It was used by Gordon Dalby in 2005 (http://www.abbafather.com/viewtext.cfm?pageID=DDBCF498-849B-4087-903B64CBAADB8718) but is probably older. Variants of it certainly are: Spurgeon apparently said that, “a little faith can bring us to heaven, but great faith can bring heaven to us.”

A post on the Idealab blog in February 2007 offers one woman’s experience of church and kingdom. It starts:

I went to church for about twenty years. At church they often would talk about how to be sure you’re going to heaven. They wanted to make no-one was confused about this vitally important topic.

They taught it’s necessary to believe certain things and then pray a particular prayer. They said God will always answer the prayer if you mean it.

Someone summarized what you need to believe and the prayer into four Spiritual Laws:

God loves you and offers a wonderful plan for your life.

Man is sinful and separated from God.

Jesus Christ is God’s only provision for man’s sin.

We must individually receive Jesus as Savior and Lord. (this is the prayer)

These laws are all about me and fixing my problem. They remind me of commercials which assure me that my life will be so much better or easier if I buy what they are selling.

Lots of people don’t seem to know the Four Spiritual Laws. Or maybe they do and they just disagree with them. Most of them who believe in heaven seem to be hoping that if they are good people and are kind to others, that will get them there.

I found places in the Bible where it seems like Jesus agrees with them. One time Jesus said people who did the following things would go to heaven:

Gave food to a hungry person

Gave drink to a thirsty person

Invited a stranger in

Gave clothes to someone who needed them

Looked after a sick person

Visited someone in prison

Jesus didn’t say anything about what they’d believed or whether they’d prayed any particular prayer...

For the rest of the post go to http://conversationattheedge.com/2007/02/04/jesus-way-to-heaven/

The quote from Madeleine L’Engle is cited by Gibbs & Bolger 2006:65.

The quote from Luther is cited by Gibbs & Bolger 2006:70. However, they don’t give a source for it and I haven’t been able to track it down. Personal correspondence from Ryan Bolger (03-01-07) yielded the following:

I’m not sure on the exact source of Luther’s quote—I’ve seen it referred to in many places. Margaret R. Miles refers to it in her book, “Image as Insight: Visual Understanding in Western Christianity and Secular Culture” (1985) on page 95. If you find her book, she might have the exact source.

I haven’t tracked it any further.

offers a good introduction in an article in The Christian Century: “The New Monastics: Alternative Christian Communities.” It can be found at:

http://www.christiancentury.org/article.lasso?id=1399

smallboatbigsea’s website is at http://www.smallboatbigsea.org/home/

The Northumbria Community’s rule can be found at

http://www.northumbriacommunity.org/WhoWeAre/whoweareThe%20Rule.htm

mayBe is a group in Oxford trying to explore new monasticism. They offer some explanation of their way at

http://www.maybe.org.uk/cms/scripts/page.php?site_id=mb&item_id=monastic

Brewin, Kester 2004, The Complex Christ—Brewin was one of the founders of Vaux, an emerging church in London with a strong focus on the arts (“we had a logo before we had a venue”). He offers an insider’s view of the current state of the emerging church and what it might become if it continues to emerge.

Frost & Hirsch 2003, The Shaping of Things to Come—stimulating and provocative book which urges a change from Christendom mode to missional mode. This involves moving from being attractional, dualistic and hierarchical to incarnational, messianic and apostolic. Although a little heavy at times the book is full of ideas and provocative propositions. For instance, a missional church needs APEPT (apostolic, prophetic, evangelical, pastoral and teaching) leadership as per Ephesians 4, rather than just a pastoral and teaching leadership which serves to (try to) maintain the status quo of the Christendom church.

Frost 2006, Exiles—Michael Frost’s reflections on living as a Christian in a post-Christian world. Michael is part of smallboatbigsea in Australia.

Hinton & Price 2003, Changing Communities—not emerging church as such, the organisation New Way of Being Church encourages experiments in community living and community action inspired by the base ecclesial model developed in South America. This book offers a series of accounts of different approaches to living the gospel.

Moynagh, Michael 2004, emergingchurch.intro—Despite the title this book is not specifically about the emerging church movement. It is actually a very good introduction to the whole area of Fresh Expressions and Mission Shaped Church.